Do you remember the Ding-dong ditch?

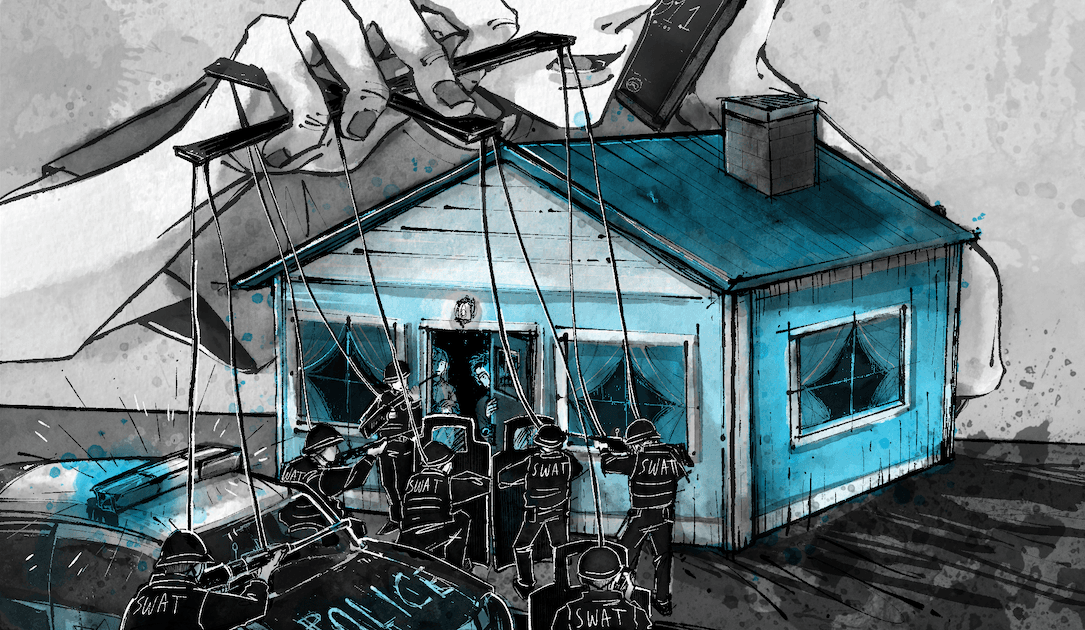

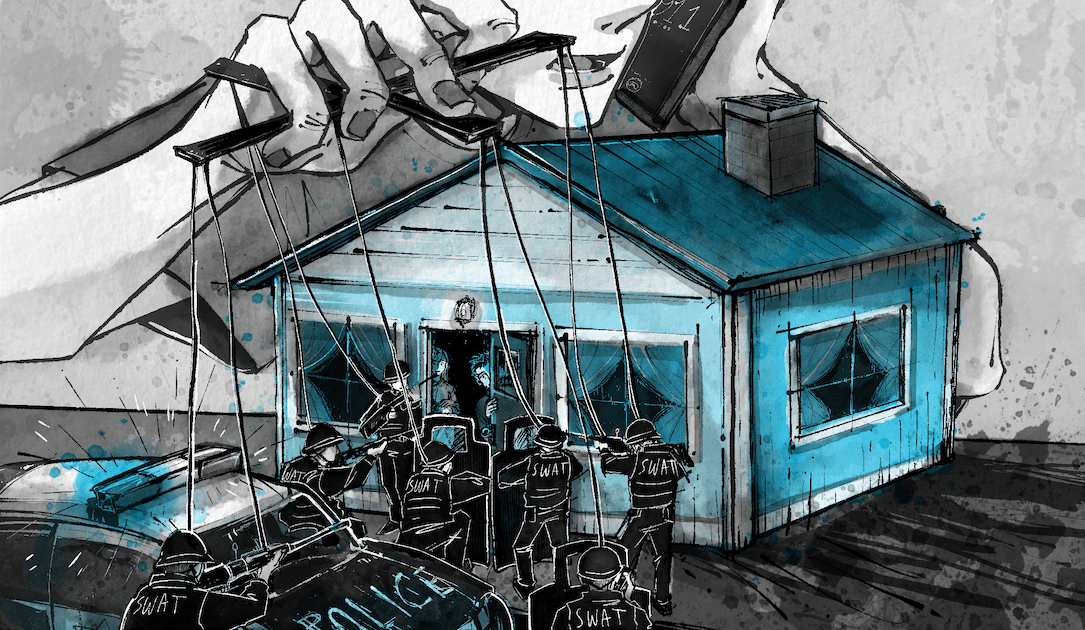

The children would ring the doorbell – perhaps several times in a single afternoon – and then run away. This childish prank gave way to what we call crushing. Someone calls the police with a prank call about a violent crime in progress, and the officers respond, appearing on an unsuspecting victim’s doorstep with guns drawn.

Crushing is nothing new. This has been going on for some time, first in the gaming community and then later among SIM swappers and other members of the cybercriminal group.

After hundreds of schools across the country suffered crashes last spring, lawmakers, law enforcement and technology companies said they would find new ways to solve the problem.

Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer recently stood on the school steps and called for more federal resources to combat the problem. Until last May, there was no national mechanism for reporting crash incidents, nor any centralized database that could help law enforcement intervene before they happened.

The FBI has now created a national repository for local law enforcement to voluntarily report swatting incidents, but Lauren Krapf, director of policy and impact at the Center for Technology and Society of Anti -Defamation League, says this is just the first step.

In an interview with the Click Here podcast, Krapf explains that crushing requires a multi-pronged solution.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

CLICK HERE: Piracy got its start among gamers trying to eliminate rivals from video games, then they targeted businesses, and now it’s what we have today. If it feels like the crush has gone through a similar life cycle, is that the right way to think about it?

LAUREN KRAPF: I think you’re right about that. It really started in the online gaming and hacking communities. Often, individuals would live stream themselves playing games, and their opponents wanted to see some sort of SWAT engagement. There would be a police raid – even going in (and) breaking down the doors. It really started out that way, as sort of a joke, and then it got serious. We have experienced cases of crushing since the early 2000s. But it has become easier and smoother over time. And it became more popular. More media coverage leads to more people engaging in this form of digital abuse.

CH: When you talk about how it’s becoming more and more popular, do you have any indicators on that?

LK: Well, it’s very difficult to get metrics because there is almost no real centralized reporting system when it comes to crushing. We don’t have data, but we saw hundreds of cases last fall. It really tends to go up and down.

CH: I always heard that crushing was sort of a young man’s game, like in the under-18s. Is this still the case?

LK: It’s really hard to follow. Anecdotally, we found that those convicted were younger and male. But we see that it is not a majority of adolescents. These are truly adults who engage in this act. And that’s one of the problems that we found with this gap in current state and federal laws. Often, the legal protections against swatting are the same as a prank or prank call to 911. But it is a completely different act. There is a different level of intention and obviously the response is incredibly different.

CH: How do you combat the motivation side? If they were terrorists, you would understand that their motivation is to feel excluded. You have no future and someone is preying on young men. But it’s like a “ding-dong gap” on steroids.

LK: I agree. The original players and hackers found it funny. But nowadays it is resulted in death; this resulted in bodily injury. Some people find it funny, but some crushers target people because of their race, sexuality, or religion. And this way, I have to guess that they don’t find it funny and that they are really trying to scare their target. To put some numbers behind this, the ADL released its annual Online Hate and Harassment Survey this summer, which examines America’s experience with online harassment. We have seen an increase in the number of people who have already been run over. Five percent of American adults reported being run over in their lifetime, 2 percent in the past 12 months – and with children, it’s even higher.

CH: You work for the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), a civil rights group. How did you become a crushing expert?

LK: I became an expert on swatting because when I joined the ADL, we decided to devote more time, resources, and effort to focusing on individuals being targeted and attacked online due to their race, ethnicity, gender or religion. So it immediately became an ADL issue. And as we sought to determine what the biggest threats were at play, swatting kept coming up as a form of digital abuse. There were gaps and loopholes in the law, and so we saw an opportunity to try to close those gaps and create better protections for victims and targets.

CH: So how can we achieve this legally? When we covered violence as a service, federal law enforcement used laws such as computer abuse, stalking, or extortion to prosecute. Is this how you do it?

LK: It seems that a patchwork of laws is required to achieve this. Often a swatter will use a bomb threat to attract the emergency response team. But because it’s a mosaic, if there are no deaths, it becomes much more difficult to hold an individual accountable. This is truly a patchwork of laws currently in use, but it leaves a lot of room for loopholes.

CH: Is Europe doing anything to solve this crushing problem? They seem to have got ahead of us on the issue of privacy with GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation). Did they address the issue of overwriting in any meaningful way?

LK: I think the best model legislation is the one that has been adopted in many states. So there are strict anti-swatting laws in Washington, Texas, Maryland and other states across the country. And I think that takes into account things like the actual emergency that is communicated to 911. And it also considers that the swatter has a reckless disregard for what might happen or what might happen on the other side. So I think there is solid legislation in the United States. You just need to have federal protections in play.

CH: Do you have any legislators who signed and said: Yeah, we think it’s a problem? Senator Chuck Schumer vaguely had this on his radar screen.

LK: We know that this is on the radar of federal lawmakers and we’re really comforted to know that this is something that they consider (to be) a priority and important. We have yet to see the introduction of swatting legislation at the federal level since around 2016-2017. A bill was introduced in this Congress, but since then we have not seen one. And at the same time, with this rise in concerns about digital abuse and also knowing that AI systems can help facilitate overwriting, we’re seeing this concern at the federal level. But it’s actually a multi-effort approach. We need to track and record these incidents. We must ensure that when this happens, victims and targets have recourse.

CH: You asked my next question. Last May, the FBI set up a virtual command center for this purpose. It’s supposed to be a sort of central information hub for tracking crash episodes, and even creating a real-time picture of crash incidents. Is this the right path?

LK: We think it’s important. And my understanding is that they provide tools and resources to agencies so that they can track crashes. At the same time, it is voluntary. I really hope it will be used robustly. A federal effort to truly track and determine tactical responses to the crash is a very important next step. Obtaining information and moving forward with increased protections would be the next step. (Note: In an interview with Click Here, FBI agent Matthew Lehman said the bureau has traced about 200 incidents since May. “By sharing the methods by which incidents occur,” he said, “it allows law enforcement to know how this has happened in other places so they can position themselves. “)

CH: Do you work with the police to try to help them find best practices?

LK: Yes, the ADL partners and works with law enforcement agencies and coalitions across the country. The hope is that there can be better increased training – whether it’s different tactical responses for that initial interaction with 911 (or) engaging in a different way when a SWAT team arrives at a certain place. Today, of course, the challenge for law enforcement agencies is that they must respond to emergency situations. Because if this is not a (crushing incident), and it is in fact a genuine incident, lives are at stake.

CH: Do you have any specific items that might help?

LK: Well, I certainly think we need state and federal legislation that actually exposes these loopholes and loopholes when a given law deems swatting to be the same thing as a prank call to 911. We We need these protections, not only for victims and targets, but for ourselves as well. need it so that there is a shared understanding: What is the definition of swatting? When does this take place?

I also think there needs to be better reporting and tracking across the country. We are pleased to see that the FBI is seeking to provide these resources to agencies. And I would say the third thing is some sort of community engagement – a way that law enforcement and people who have been targeted or might be targeted by swatting can come together and create some sort of such painless response and harmless to the victims. and targets as much as possible, while allowing law enforcement to do their job and respond to emergency calls.

Future saved

Intelligence cloud.