Article 44 of Immigration and Refugee Protection Act States:

Preparation of the report

44 (1) An officer who considers that a permanent resident or a foreign national who is in Canada is inadmissible may prepare a report setting out the relevant facts, which report shall be transmitted to the Minister.

Order of dismissal or remand

(2) If he is of the opinion that the report is well-founded, he may refer it to the Immigration Division for an admissibility inquiry, except in the case of a permanent resident who is inadmissible to the country only reason: having failed to fulfill the residence obligation provided for in section 28 and except, in the circumstances provided for by regulation, if it is a foreign national. In these cases, the minister can issue a removal order.

Terms

(3) An officer or the Immigration Division may impose on a permanent resident or foreign national who is: the subject of a report, an admissibility inquiry or, being in Canada, a removal order.

Conditions — inadmissibility for security reasons

(4) If a security inadmissibility report is referred to the Immigration Division and the permanent resident or foreign national who is the subject of the report is not detained, an officer also imposes to the person the prescribed conditions.

Duration of conditions

(5) The prescribed conditions imposed under subsection (4) cease to apply only when:

(a) the person is detained;

(b) the report of inadmissibility for security reasons is withdrawn;

(c) a final decision is made not to take a removal order against the person for inadmissibility for security reasons;

(d) the Minister makes a declaration under subsection 42.1(1) or (2) in respect of the person; Or

(e) a removal order is executed against the person in accordance with the regulations.

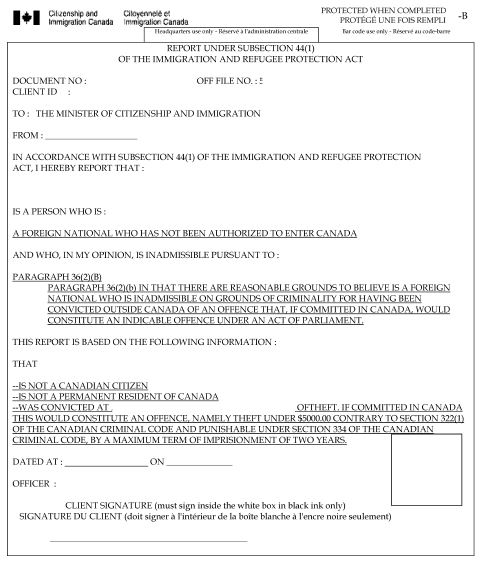

Inadmissibility reports look like the following:

The Canada Border Services Agency typically issues statutory declarations explaining the circumstances leading to the A44 report, which look like this.

These two documents are generally the reason for the A44 report and should be obtained by deportees in order to determine next steps, including requesting authorization to return to Canada or judicial review.

Statistics

Judicial review of inadmissibility reports

In Lin v Canada (Public safety and civil protection)2021 CAF 81, the Federal Court of Appeal declared that judicial review of the CBSA’s decision to issue an inadmissibility report to a person under subsection 44(2) of the IRPA and refer it to the Commission immigration and refugee status should only be granted in exceptional circumstances. The Court stated:

In the present cases, the Minister’s delegates, acting under section 44, expressed their belief, based on the evidence, that the circumstances are sufficient to justify a more formal investigation and a decision of inadmissibility rendered by the Immigration Division and, if necessary, the immigration appeal. Division. The process is similar to a selection exercise in the sense that there is no finding of inadmissibility or modification of status. Appellants will be given a full opportunity to present evidence and present their factual and legal arguments and concerns regarding the relevant issues before the Immigration Division and the Immigration Appeal Division. This includes any procedural fairness or substantive issues regarding the section 44 selection process that compromise the ability of the Immigration Division to proceed. This also includes whether there were any misrepresentations giving rise to the grant of permanent residence, the relevant knowledge of the appellants and any humanitarian considerations. Thus, in the present cases, the proceedings before the Immigration Division and the Immigration Appeal Division are both available and adequate.

The general rule is that judicial review should not be initiated until all available and adequate administrative remedies have been exercised. The prohibition set out in s. 72(2)(a) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act which prohibits judicial review until all administrative appeals have been exhausted.

(citations omitted)

Nonetheless, several Federal Court decisions have stated that when a person does not have the right to appeal to the Immigration Appeal Division, or when the Immigration Appeal Division is prevented from take into account humanitarian considerations, judicial review is possible.

In Zhang v. Canada (Public Safety and Civil Protection)2021 CF 746Justice Ahmed determined that the CBSA has jurisdiction to take into account humanitarian and compassionate considerations in organized crime referrals, and that judicial review of its decisions was possible.

Humanitarian considerations

In Singh v Canada (Public safety and civil protection)2019 CF 1170, the Federal Court stated that the CBSA has the discretion to consider humanitarian and compassionate factors when issuing A44 declarations. The Court stated:

Case law recognizes that even when officers and delegates confirm the facts underlying the alleged inadmissibility, they retain some form of discretion not to refer a person for an admissibility investigation. This encompasses situations where officers or delegates believe that other considerations, such as the potential for rehabilitation or important humanitarian factors, are more important in maintaining the objectives of the IRPA: Melendez v Canada (Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness), 2016 FC 1363 (Melendez) at para 34.; updated in McAlpin, supra, at para 70.

There is, however, considerable debate over how much discretion officers and delegates actually have, and under what circumstances they should or should exercise that discretion. The Chief Justice in McAlpin, supra, summarizes this current tension:

Having regard to all of the above, and in particular the guidance provided by the FCA in Sharma above, I consider it necessary and appropriate to update and expand on the conclusions reached by the judge Boswell regarding the current state of the case law regarding the scope of the discretionary power provided for in s. 44(1) and (2) in cases involving allegations of “criminality” and “serious criminality” by permanent residents. Maintaining the framework adopted by Justice Boswell, I would summarize this jurisprudence as follows:

1. In cases involving allegations of criminality or serious criminality on the part of permanent residents, there is conflicting case law as to whether immigration officers and ministerial delegates have discretion under s. 44(1) and (2) of the IRPA, respectively, beyond the simple verification and reporting of the fundamental facts underlying an opinion that a permanent resident of Canada is inadmissible or that the report of a agent is well founded.

2. In any event, any discretion to take into account CH factors under s. 44(1) and (2) in such cases is very limited, if not non-existent.

3. Although an officer or ministerial delegate may have very limited discretion to consider H&C factors in such cases, there is no general obligation to do so.

4. However, when humanitarian factors are taken into account by an officer or a ministerial delegate to explain the justification for a decision made under s. 44(1) or (2), the assessment of these factors should be reasonable, having regard to the circumstances of the case. When these factors are rejected, an explanation should be provided, even if very brief.

5. In this particular context, a reasonable assessment is one that takes into account at least the most important CH factors that have been identified by the alleged inadmissible person, even if only by listing these factors, to demonstrate that she was considered inadmissible. . Failing to mention the important CH factors that have been identified, when purporting to take into account the CH factors that have been raised, may well be unreasonable.

(Emphasis added in bold.)

The Minister argues that officers and delegates need not consider or refer to facts other than those underlying the alleged inadmissibility before making a removal decision: McAlpin, supra, at para 70 (item 3); Pham v Canada (Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness), 2016 FC 824 (Pham), at para 18; Apolinario v Canada (Public Safety and Civil Protection), 2016 FC 1287 (Apolinario), at para 46; Balan v Canada (Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness), 2015 FC 691 (Balan), at para 16; and Lin et al v Canada (Public Safety and Civil Protection), 2019 FC 862 (Lin et al), at para 16. I agree with the Minister that the case law does not require officers or delegates to take take into account observations or humanitarian factors, except where the evidence is prima facie convincing: Lin et al, supra, at para 16, citing Faci v Canada (Public Safety and Civil Protection), 2011 FC 693, at para 63; McAlpin, cited above, at para 70 (point 5), 74.

(…)

In the present case, the ID is not in a position to consider Mr. Singh’s arguments nor to rule on the application in his favor. It was clear that Mr. Singh’s conviction rendered him inadmissible: IRPA 36(1)(a). In cases where a person is effectively inadmissible, the ID must issue a removal order: s. 45(1)(d) of the IRPA. As such, the delegate was the final decision-maker authorized to consider his observations and other H&C factors and, on that basis, decide not to issue a referral for revocation. Mr. Singh’s only real chance of avoiding removal was to provide representations to the delegate and hope that the delegate would exercise his discretion not to refer him to an admissibility inquiry.

In other words, where the applicant’s underlying inadmissibility is not in question, it is the delegate, not the ID, who is best placed to review the relevant submissions and considerations. humanitarian order. I emphasize again that in the absence of compelling prima facie evidence, the delegate is not obliged to do so. However, once the delegate chooses to consider the observations or CH factors, it is imperative that he or she does so reasonably and that his or her reasoning is justifiable, transparent and intelligible: Dunsmuir, supra, at para 47; NL Nurses, supra, at para 14.

Although they are not obliged to take into account humanitarian considerations, particularly in cases where a foreign national is presumed inadmissible for criminal reasons, they have the discretion to do so (McAlpin v Canada (Public safety and civil protection), 2018 FC 422 at para 65; Melendez v Canada (Public security and civil protection)2016 FC 1363 at para 34).